American Gem Stories: The Ant Hill Garnets of Arizona

Mining is hard work in any climate, but it would seem particularly grueling under the heat of the Arizona desert. There is, however, one group of miners who have been at it for millennia who don’t seem to mind the heat at all: ants. Specifically, Pogonomyrmex barbatus, the red harvester ant.

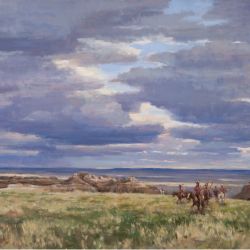

The Four Corners region, where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona meet, can appear utterly lifeless from high above, nothing but sand and stone broken here and there by strips of green clinging to the banks of the San Juan River and its tributaries, but the area is home to a diverse ecosystem of green pastures, sparse scrubland, and forests of pine and juniper clinging to hillsides at the higher elevations.

It is also home to the typical cast of Southwestern critters: eagles, bobcats, snakes, coyotes—and the red harvester ant. These large ants spend their days diligently digging their colonies, burrowing up to eight feet into the ground and producing mounds as large as four feet in diameter.

Courtesy of MYEL Design

Courtesy of MYEL Design

The Accidental Miners

As they burrow underground, they carry sand particles and other bits of earth and deposit them on the surface, forming mounds. Sometimes, among the particles they move, are small red bits a little larger and heavier than the other grains they move. I’d like to imagine that the ants think they’ve come across one of the seeds they like to eat (after all, the word “garnet” and “pomegranate” both come from the same Latin word for “seed”), or perhaps a particularly lazy member of their species, and get a little frustrated when they have to haul one of these things to the surface. It then gets dumped on the side of an ant hill, where it stays until rainwater deposits it at the base of the mound and washes it, where it will remain until a glimmer catches someone’s eye.

Those little red rocks might be just another obstacle for an ant to remove, but to us, it’s pyrope, the aluminum-rich, pomegranate-red variety of garnet. One ant’s trash is another man’s treasure, I guess.

Discovery by the Navajo

The Navajo, who call themselves the Diné, arrived in the Four Corners region from the Pacific Northwest around 1400 AD. Originally hunter-gatherers, they eventually began to produce food using agricultural techniques they learned from the nearby Pueblo. It’s not clear exactly when they would have first come across an ant hill garnet in a red harvester ant’s trash heap, but it’s easy to imagine a hunter-gatherer keeping one eye on the ground and spotting a shiny red stone at the base of an ant hill, or a farmer tilling up the ground and turning up a rock that looks different from the others.

By the end of the 19th century, turquoise would overtake garnet as the stone of choice in Navajo decorative arts, but for a good part of their history, the Navajo used ant hill garnets in everything from personal decoration to ceremonial rattles. By the time the Spanish arrived in the area, ant hill garnets were being traded all over the Southwest by the Navajo, Pueblo, and Hopi.

Courtesy of Sami Fine Jewelry

Courtesy of Sami Fine Jewelry

The Geological Origins of Ant Hill Garnet

Much like the northeastern corner of North America, where Elijah L. Hamlin discovered tourmaline in the hills of Maine, The Colorado Plateau is an unfathomably ancient land. The rocks at the bottom of the grand canyon, at the southwestern end of the plateau, are some 2 billion years old.

For much of its history, the point where the Rocky Mountains meet the Great Plains was a coastline. For millions of years, the crust of the seabed that covered most of the central US and Canada pushed up against the continental crust, building up the continental crust and eventually creating the Rocky Mountains and the Colorado Plateau. Millions of years after that, the area was the site of many active volcanoes, almost all of which are dormant or extinct today.

This long, active geologic history has produced some of the greatest natural wonders of North America, from the Grand Canyon to the mesas that rise from Monument Valley like the tombstones of titans. While many of the surface features were the result of the movement of vast quantities of water, deep below the earth, the intense heat, pressure, and volcanic activity resulting from the collision of oceanic and continental crust created the tiny treasures unearthed by oblivious ants.

A Rare Treasure

Ant hill garnets are rare, but not for the reason most gemstones are rare. When you get down to it, they are just your typical pyrope garnet. But what makes these special, and what makes them a collector’s item, is the way they are produced. For one thing, ant hill garnets are not commercially mined. I mean, how could they be? Ants work hard, but they only work for themselves. And if a human digs one up, it’s not an ant hill garnet, is it? On top of that, they are only found within the Navajo Nation, which occupies most of the northeast quarter of Arizona but also reaches into New Mexico and Utah. Only members of the Navajo Nation can collect these stones.

So much of the value of a gemstone comes not only from its rarity or beauty, but from what it symbolically connects you to. On first glance, an ant hill garnet might not appear any different from another garnet. But they are produced in such a unique way, and in such a unique part of the world, that you’ll always have a story to tell when you wear it.

Ant Hill Garnet Rough Courtesy of Song of Stones

Ant Hill Garnet Rough Courtesy of Song of Stones

Thoughts on “American Gem Stories: The Ant Hill Garnets of Arizona”

-

The story is engaging, the narrative reflects considerable research, and the language is eloquent. Wonderful article. Look forward to reading more. Are any garnets found in places where the hiker can keep their find?

-

Thank you for your kind words. I do not know if there are hiking areas with finders keepers rules. It would be unusual- as folks tend to like to protect their claims- I wouldn't want to contend with a colony of angry ants!

-

-

My grandfather found two of what I think are anthill garnets when he was working in that area about 1900. My mother had them set into a ring. I appreciate this article because I never knew anything about the stones except the family story.

-

I me and my mom are a bit older so getting out and doing things is a lot harder for us by older I mean we have Rheumatoid arthritis and our bones are always giving out anyways we'd love to go and find a place like this we live in Solo Arizona and we're wondering if there are Anywhere like this near where we live just wondering if you'd Let Me Know if you're aware of anything Close by Thank You and have a wonderful day